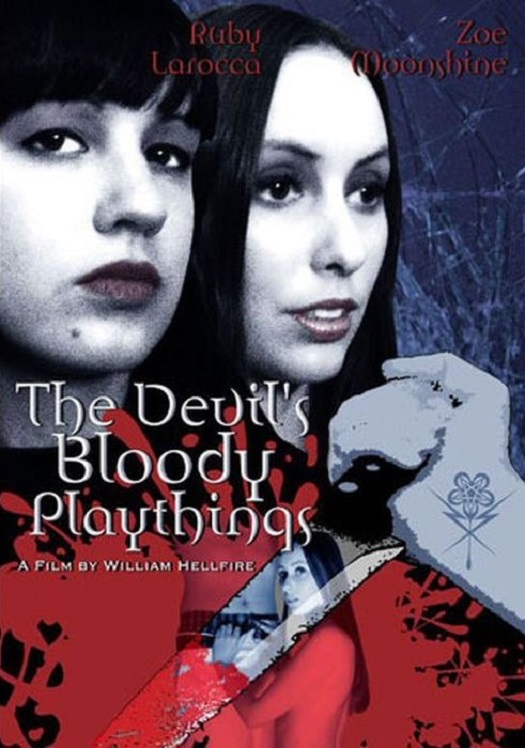

Self-destructing renditions of life and death on video: The Devil’s Bloody Playthings (2005)

- Well, I saw a man walking on the water, walkin‘

Coming right at me from the other side

Calling out my name

And, „Do not be afraid, now!“

Feet begin to run, run, run

Pounding in my brain

(Richard Hell & the Voidoids – Walking on the Water)

We were already expecting her. Seated on top of Christine’s (Ruby Larocca) shoulder, stuck in the couch, inhaling the fumes of a graciously splayed into focus cigarette. During the opening seconds of William Hellfire’s „The Devil’s Bloody Playthings“ nothing much happens aside from Larocca’s immobile body waiting for her flatmate to return home and yet it manages to convey and sustain a jittery feeling more effectively than many expensive, more nimble or fast striking variants of roughly the same narrative structure. That Christine is a peculiar creature, bluntly she talks up on her framed in true Riefenstahlian angles victim, always coming out on top by force of subverted traditional camera set ups or a little video taped aid out of her own hand. But the girl isn’t having this brand of blackmail anymore and promptly packs her bags. Courtains up for Karen (Zoe Moonshine) who is conveniently looking for place to stay in her new surroundings. That’s about all there is to know about Hellfire’s minimalist storyline, the rest is psycho terror forced on Karen but also, through use of clever staging tactics, us.

There is a consistency running through Christine’s playdolls, they’re always taller than her, sometimes notably and the visibility of this trait increases when put into new, unsettled environments, their tormentor’s seedy circle of friends for example. Hellfire has them carefully framed throughout, their physique acting as gauge of alienation, an untrustworthy one though, manipulated by himself or Christine who in unholy camaraderie forces her nouveau tool to wear high heels normally associated with female empowerment and doubly so on women already exceeding the socially acceptable height range. She is that certain roomie trying to double for your parents, both of ‚em, your strict mother and lenient father, in one person, at the same moment in time, dressing and undressing you but always with ulterior motives. Aiding these encroaching behavior patterns is a strange rhythm of uneasyness – roofie induced yawning spliced between a lenghty, supposedly funny bar anecdote Christine is sharing, Karen’s bare feet tapping on each other in irregular intervals during a phone conversation with her real mother. A senseless, downright compulsive counting measure interrupting the flow of imagery.

Sounds come likewise exalted – a zipper, the click-clack of heels, Christine slapping Karen’s hands when the latter tries to keep her to be revoked panties in place, many a touch. Larocca grabs, pulls, bends incessently and most of it is discernible with utmost clarity among heaps and heaps of droning soundscapes. Parasitic frequencies mirrored, doubled and called in question once more by actual ones belonging to the score. Sharpened sound spikes akin to and sometimes imitating outright the noise drops accumulating in a claning metal barrel ready to overflow do. Quite obviously lacking the budget necessary for all too staggering visual overpowering tactics, „The Devil’s Bloody Playthings“ predominantly relies on sonar guerilla assault for affective impact, but in its most intricate sequences these impressions conspire with just a bit of inspired camera and editing work to remarkable effect. That before mentioned barrel is the little appartment our two clashing parties dwell in, a pronounced sense of space and more importantly altitude governs all interaction in-between its four walls.

In all her statuesque frame Karen lingers head bowed in the shadows while Christine slouches on the couch with gusto, laughing at intimate photographes she took without consent on the loo. „You’re supposed to laugh – it’s funny.“ – the couch is a central hub of interplay, a gloomy lair nivellating all difference in purely physical power. It’s always the same – placed next to each other in a single frame, almost docile conversations, maybe a little camera ping pong from face to face. No danger far and wide. And suddenly background orchestrations of both the physical and meta-physical chess master turn the scene upside down. Not more than an elliptical cut and Moonshine’s half-naked right beside the still dressed, as if frozen in continuity, Laroca. Cocaine and liquor shot infused escalation, an arcade-machine-like rattling as unnerving undercurrent beyond the heavy drum ’n‘ bass stream. Click and flash – pictures are being taken again; always from above when the victim is already lying low, often accompanied by a white flash of the screen. Only for the blink of an eye, before the proceedings reassemble in front of ours, imitating the nature of polaroid exposure. Then Christine aims the camera directly at us and or more specifically Karen whose helpless point of view cinematographer Alex Cam recreates. A longer white influx, close to a whole second; the effect clears off just as the photographer herself is watching the developing chemicals do the same.

Interactive filmmaking like this is at the core of William Hellfire’s approach, his film is an alternation. Sometimes we have to remain still, beaten into submission by directorial force; sometimes we’re right among these oppressing elements ourselves, tricked into the belief of descretionary. It’s the same for the two leads who oscillate from calm to hyperbolic. „What do you think you’re doing, why are you touching me like that!?“, bursts the formerly enticing Christine into a fit of rage – once more by her side: We, glued right next to her mouthless head. Disembodied accomplice, mouthpiece – a little shoulder devil popping up out of the blue. Of course „The Devil’s Bloody Playthings“ looks like cheap video, nevertheless it represents, at times, a bigger slice of life than less digital, and thus deemed as irrevocably fake, pictures. Cinema verité for your cheapo underground movie party. A flawless emulation of bystander apathy, after all our own perception is rather purpose-build by default too. A voyeur too occupied to really interact himself – a description that fits more than one entity involved in these games.

Combining all these differing, nay contradictory notions into one potent picture of compulsion, the films centerpiece has Karen masturbating to an erotic novel in her room. Rather tame in nature, just a hand doing its job shielded by panties in a medium shot, until a switch of perspective turns the session more claustrophobic by – of all things – opening up the field. Now a long shot gobbles up the entirety of her situation through the rectangular focus of a hidden security camera. Disaffectionate enough on its own, the gaze is skinned once more – cut to Karen who is watching on in a separate control room. Not selfmade videos she always claims to be quite a creator of but externally, automatically generated content strictly reliant on outside activites. The act of participating in a creative process is crucial to not only Hellfire’s mise en scène but also Christine’s mental problems. „I was watching you – I fucking taped you!“ – and yet she holds no interest whatsoever in said material. Just control – that’s all there is to it. As soon as her previous victim had finally found the courage to call her out in the opening minutes, she proceeded to smash the precious leverage.

William Apriceno – the man behind the artist – might be a hopeless enthusiast, of film, of diverse approaches to their production through vintage as much as modern devices and still his alter ego is curiously fond of portraying these as instruments less of boundless creativity than harmlessly artistic looking torture methods. Polaroid cameras as agents of degradation, a theme also touched on by his to this date latest outing „Upsidedown Cross“ (2014). And while much of his earlier work relied heavily on fetishised strangulations or other murder acts carried out and filmed in a fashion that deliberately blurs the lines between amateur kink and the mythological realm of snuff filmmaking, his (and Ross Snyder’s) up and coming documentary „Mail Order Murder: The Story Of W.A.V.E. Productions“ (a company Hellfire worked for himself) is centered around just this – Imitations of death sold to the disciples of nihilistic edgyness or perhaps: People just like Christine?

Cut the meta-excursion and back to Karen’s room. A near quadratic prison cell mostly visualized as the likewise quadratic excerpt of her deep blue mattress and the somber splendor of grey extension paint climbing up all the way to the ceiling. Quite some test chamber for assault – human, aural and visual. Howling sounds creep around while the walls turn steeper and steeper with every new bizarre angle, screen flashes lacking a triggering cam, the agile camera races across the oceanic surface like a proper Jaws, Karen trying to drown out the sound in vain. There is another layer to the complex sound desing and it is only grasped in full when it’s already too late. An overlaid head canon, melodic mumblings from a damaged brain. Steps in an escalation like the black frames between what resembles chapter stops and like these it increases in duration as time goes on. Successive slidings of madness. Finally the percussion sheds all restraints in pounding disorder just as Christine begins to murder friends unraveling her little secret. But she’s not alone. Dressed in a school girl uniform and carrying a tray Karen has to serve tea for a singularly sleazy visitor, tall but isolated in frame with just some eggshell colored walls having her back. Christine’s on the couch with her friend, comfortable, no though talk, almost soft-spoken and sweet, juxtapositions, as she soon forces her slave to pleasure that guy with her hands. Hellfire, a veteran of cute softcore flicks too, never progressed into very graphic presentations of sexual violence, even though his dark recent work certainly offered enough opportunities. He doesn’t need them, non-penetrative and off-camera masturbation acts are more than enough for him to convey strikingly detached feelings, no shared emotions during exploitative sex in this as well as „Upsidedown Cross“.

Forced to lick some fake cum – owing to the strict abstinence from going over board exercised till now, this is a gut-wrenching scene even in its blatantly unconvincing nature – Karen finally snaps. The percussion train passes through a final time, like a barrage of wagons whirling up dust and a forceful wind right in front of you for what feels like an eternity. Rhythmic cuts, her face on the left, the mirror’s reflection to the right, flash, face, flash, blood around the eyes. When the whipped animal ultimately lashes back at its master, a slight but noticiable shift has already occurred – we are finally one with Ruby Larocca, not beside her. Now towering, Zoe Moonshine pushes back the submissive camera headfront, making the operator tumble over. Don’t wake sleeping dogs – it was her musical tide all along. All sound stops as she ends her captors life, inhales deeply but silently. Credits roll to a song that claims: „Nothing happens when you die“ Nothing, except silence so badly craved. The sweet fruit of audiovisual oppression and relief mechanics entwined.

The Devil’s Bloody Playthings – USA 2005 – 85 minutes – Direction: William „Bill“ Hellfire – Production: William „Bill“ Hellfire, Zoe Moonshine – Screenplay: William „Bill“ Hellfire – Cinematography: Alex Cam (as „Alex Fuego“) – Editing: Alex Cam (as „Alex Fuego“) – Music: – Cast: Ruby Larocca, Zoe Moonshine, William „Bill“ Hellfire, Shannon Selberg, Mave Wilson and many more

Kommentar hinzufügen