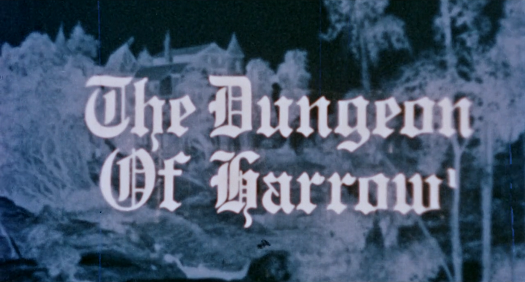

An exercise in cinematic comic book style with Pat Boyette and „The Dungeon of Harrow“ (1962)

- „I’d been in love with motion picture-making for a long time,“ Boyette recalls. „When television came in, suddenly there was a big market for films. I thought, ‚This is the thing to do. You can make some schlock and get by with it at this early stage.‘ Not that you purposely go out to make schlock. But the fact is, with limited resources, that’s the best you can hope for.“

(Pat Boyette quoted in „A fright-fest of films by Pat Boyette“ by Marty Baumann [J. David Spurlock – The Nightstand Chillers – Vanguard Productions; p. 45])

The road map to cinema knows quite a few visual artists turned filmmakers – Mario Bava was a painter, his father Eugenio a sculptor, Agnès Varda trained as a photographer just like Kubrick, Marker or Wenders did, and famed contemporary David Hamilton was employed as a graphic designer when he first glitched into Varda’s trade, then later into a short-lived stint at film direction. Texan Pat Boyette though was quite a different beast altogether: After working as a radio broadcaster for decades, he first dabbled into the visual branch as a news anchor on television before directing three films, the first („The Weird Ones“ [1962]) and third („No Man’s Land“ [1964]) generally considered lost in a storage fire, the second topic of this very text. Having only tried the trade briefly for local dailies in his youth before, he still settled as an artist for Charlton Comics when the chance arose, deserted planet cinema and seldom looked back again soon after. In consequence, „The Dungeon of Harrow“ does feel a bit like the culmination of a progression through trades en route to your true calling; less like refined cinema, more like a slew of paintings on a crude string – it is in short: A film sharing more traits with the visual than the performing arts.

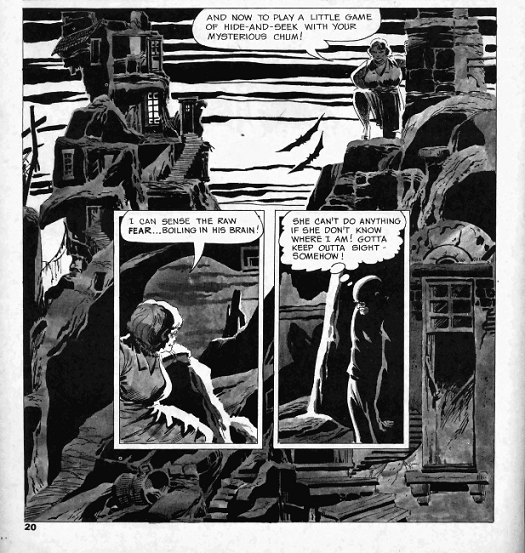

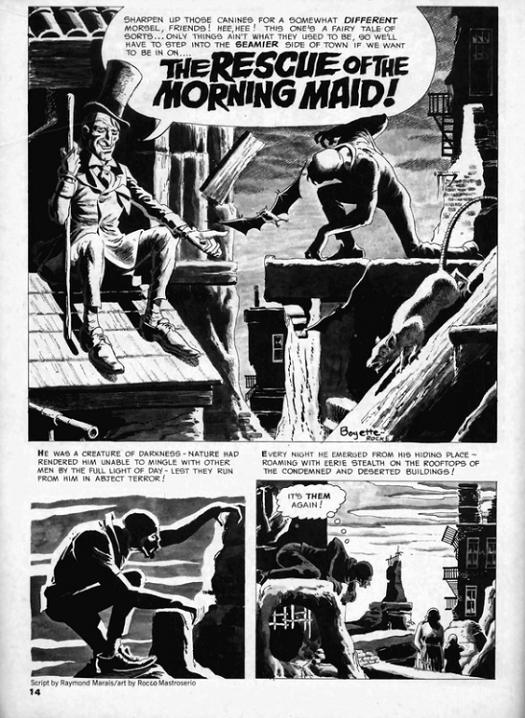

- „The Rescue of the Morning Maid“ (Creepy #18, January 1968)

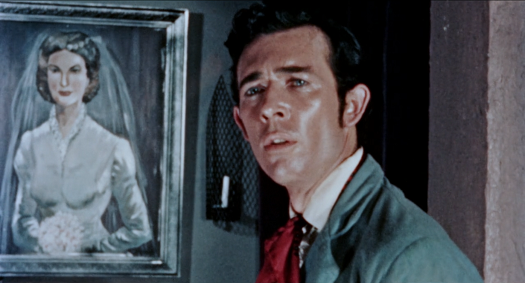

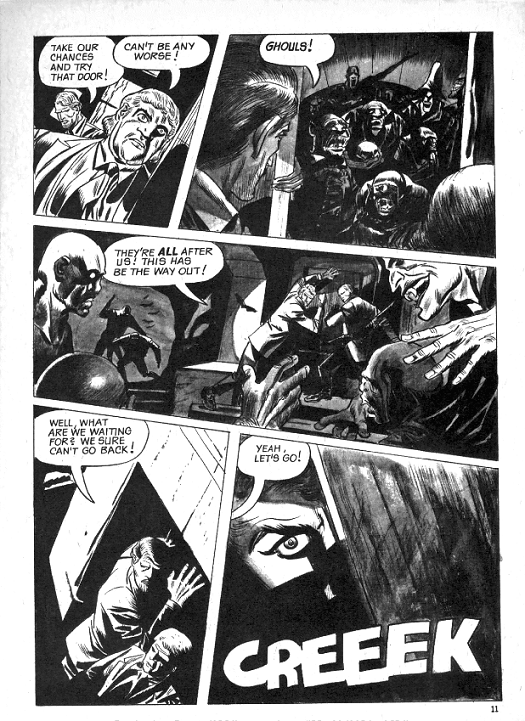

A film that opens up with the perhaps crudest matte effect of a rustic villa ever drawn on the silver screen and yet manages use these supposed shortcomings to its advantage. Coming across a hell of a lot like the cropped VHS version of a scope picture, every single frame is more akin to a well composed, extremely tight clad comic book panel. The pronounced steadyness of James C. Houston’s camera work punctuates this impression only further. Motion’s a strange beast in Boyette’s world anyhow – if the camera moves at all, it only serves a markedly placid connector following people between specific set-ups, almost as if these are still in the process of being drawn and inked right beyond our gaze. Just sketched along as the meters amass – this is Pat Boyette’s unique cinematic style in a nutshell. Perfected only a couple of years down the road, these bridging actions became a highly recognizable staple in his work as a pencil. Leaving the confines of their panels, his characters get in position for the next one in line. This lends a distinct sense of urgency to the proceedings and played an important part in the creation of that signature fast pacing which allowed Boyette to churn out remarkably complex tales in just some four to five pages.

Intermission: A lesson in visual movement with Pat Boyette

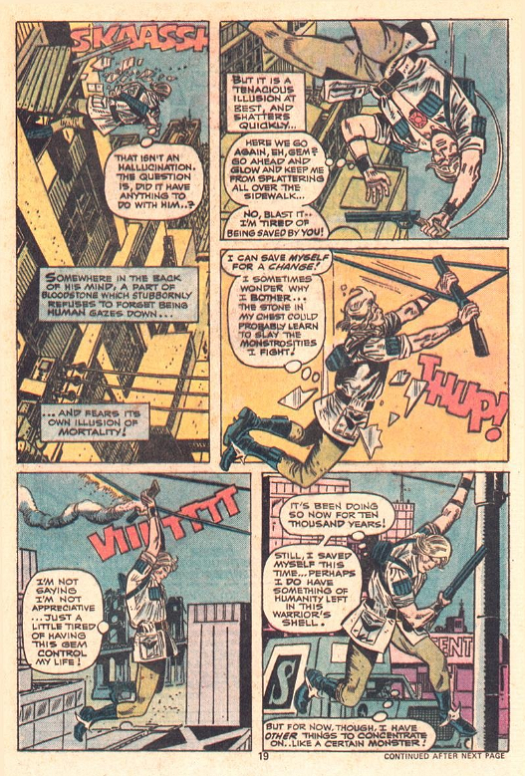

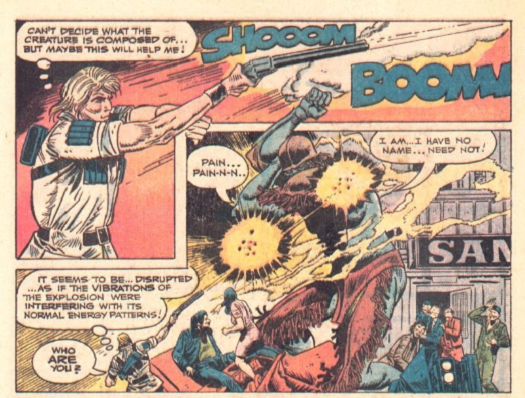

- Two excerpts from „The Lurker Within“ (Marvel Presents #01: Bloodstone, October 1975), the product of Boyettes very short-lived work with comic giant Marvel. Notice how he accelerates speed, emphasizes forward movement and guides our eyes from panel to panel by allowing his characters to leave their confines on the page. The direction of the shots as well as the position of the fists (and Bloodstone almost grabbing the very point where we are suppossed to start examining the second panel!) urge to read the second page clockwise with action and passed time moving from right to left. Then, dialogue runs back from the left to the right. Who on earth comes up with stuff like this? A true avantgardist of the medium.

- It’s obvious in every frame that „The Dungeon of Harrow“ was a borderline amateurish production with insufficient funds for complex action sequences, pay close attention though to the way Pat Boyette stages action and it soon becomes evident how he made up for a static camera and a surprisingly conservative montage. Lee Morgan pulls away the whip from Maurice Harris and by this visualizes a forward momentum, the advance of the foe in his own direction after the cut.

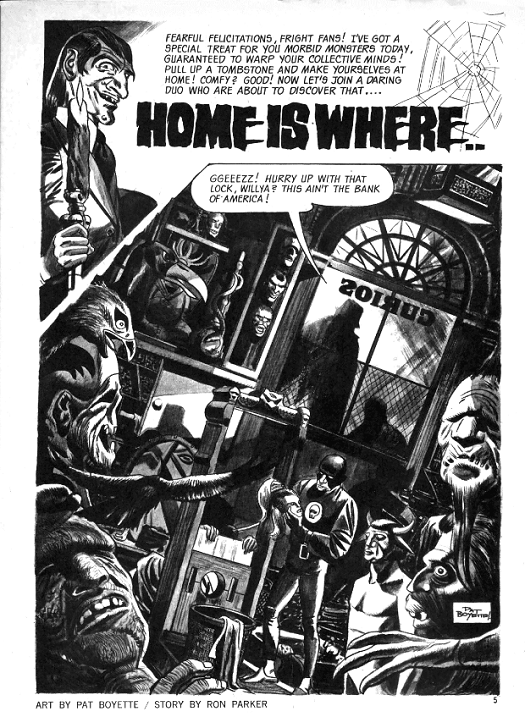

- This page from „Home Is Where –“ (Creepy #22, August 1968) employs the same technique to draw us to the ground alongside the falling men. Like in the above sequence motion goes to the left, and this is where our gaze starts out following a cut or transition to the next panel.

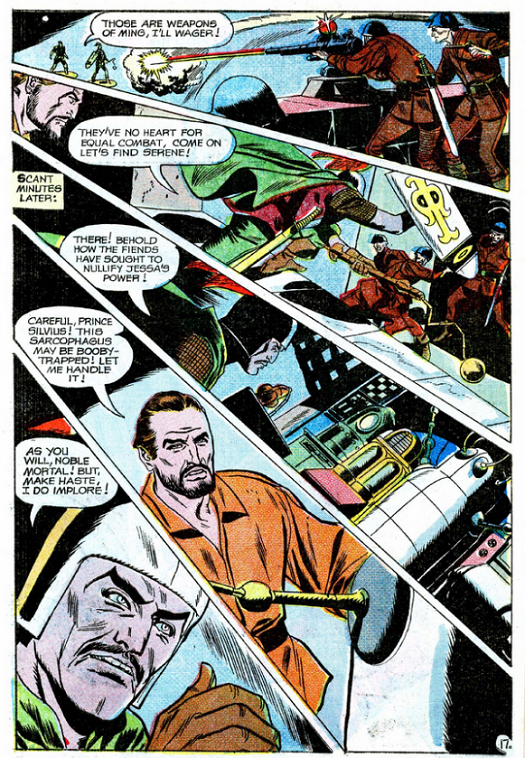

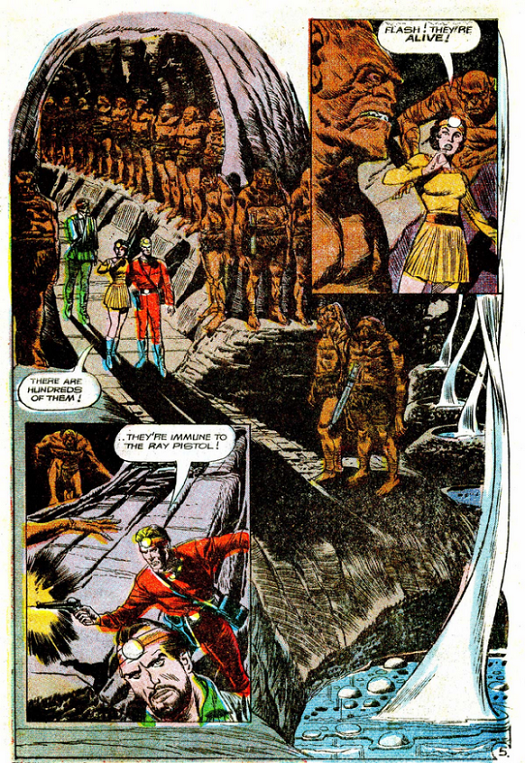

- „Mission Into the Mystic Realm“ (Flash Gordon #16, October 1969)

Frozen in their natural habitats as these later day characters may be, here everyone is still in fluid motion marred alone by the unnaturally slow feel to it. Shifting their mostly slender bodies across the screen approximately 25% slower (don’t nail me down on this!) than your regular film performer, all actors rely heavily on strong, exaggerated gestures, then suddenly grow rigid in expressive stances. You’re almost bound to expect a musical number around the corner, and yet it fails to materialize each and every single time. Instead an off-commentary (spoken by Boyette himself) highlights the inner feelings denied by the lack of more refined facial articulation. According to the situation at hand, all antics either verge into the territory of expressively full-bodied silent film acting or the sub-dued to a maximum „non-acting“ evident in some of Jesús Franco’s or Jean Rollin’s finest work. Boyette does not lead actors, he merely inks their performances. Injecting life into superficially inanimate objects – a technique he would later bring to perfection with his trademark „flat“ faces. His dialogue chimes in with the stiltedness, tongues move hardly less leisurely than their accompanying bodies in this world. Slow, unnatural, with a pronounced otherworldy ring to them („I have permitted myself to lie last night.“) the words wrest from our most treasured appendix still emit a refined, at times supremely witty glow („You’re quite certain I’m a bit of an ass, aren’t you, Captain?). But no matter the tone, all conversations share one common trait: They could easily fill the speech bubbles in any given panel with short, poignant sentences. And indeed, some little bubbles are all the compositions could still accommodate. Verboseness is never an issue, quite on the contrary – Boyette’s writing makes some of his creations transgress their roots in by 1962 firmly established gothic horror stereotypes. Being prime offenders in the snappy dialogue category, maid turned hero’s love interest Cassandra (Helen Hogan) and the blue-blooded manhunter’s implicit black slave Mantis (Maurice Harris) hence turn into far stronger characters than what their roles betray on mere surface level readings. The latter’s mocking last words directed at his master are likely among the finest in all exploitation cinema. „I always do what you say, even die.“

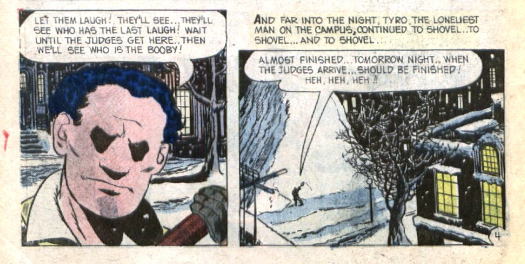

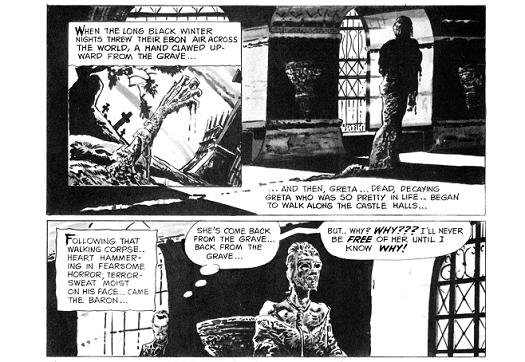

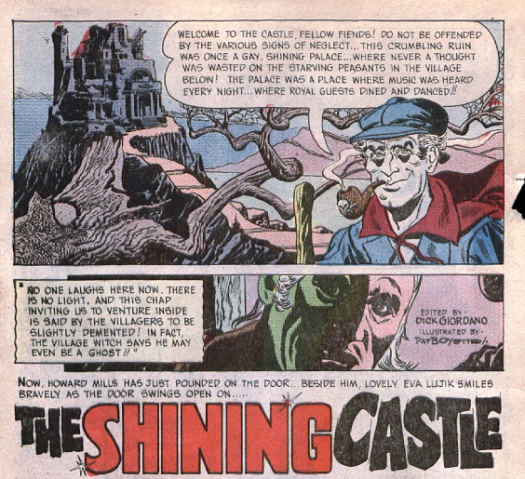

- „The Shining Castle“ (Ghostly Tales #62, August 1967)

- „Up on the Mountain“ (Ghostly Tales #63, October 1967)

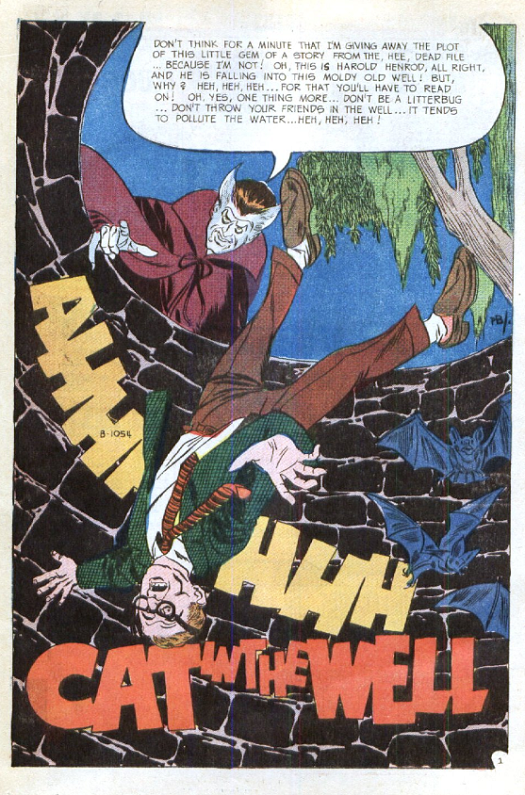

- Pat Boyette was his own letterer on most assignments and, as these examples show, had a knack for using words or drawn-out sounds as a directional guide too. All dialogue and motion in „The Dungeon of Harrow“ travels roughly as slow as sound does here. „Cat in the Well“ (Ghostly Tales #65, February 1968) & „Case: 516 – ‚Drums of Darkness'“ (The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves #01, May 1967)

It’s a rigorous longing for style, a willingness to sacrifice in other departments even, that enables Boyette to create substance in the first place. The rudimentary nature of all décors actually ends up carrying his vision instead of sabotaging it. Rooms are constructed around a small handful of highly adverse colors, just one for most surfaces and hardly ever the same for connected segments of wall – creating a triangle effect whenever someone is filmed in or in front of a corner. More a way of geometrically dividing compositions rather than bathing them in expressive filmic illuminants, this process becomes a remarkable early simulation of the attention diverting and guiding color schemes later employed in his comic work. Suspiciously absent remain multi-colored glass or lighting excesses à la Bava or Corman while the impressions evoked by protruding areas are highly favored. The striking dark green tablecloth dominating a whole chamber, the kitchen’s artlessly plastered walls, the interaction of countless unintricate backdrops in the titular dungeon whose moody atmosphere seems to be created entirely through this and the most basic of lighting techniques. Ones almost akin to a simulation by an array of paint layers on papier-mâché rocks. Intricate smaller decorations housed in unsophisticated surroundings – perhaps an adequate characterization of Boyette’s body of work itself. In any case, the secret to the artistic success of his all too fleeting try at motion picture making.

For recreating the look of their childhood’s pulp comics is something quite a few directors set out to achieve, sometimes coming awfully close – like George A. Romero’s „Creepshow“ (1982) did. Nonetheless, a side by side comparison can only hightlight „The Dungeon of Harrows“’s qualities: Far more akin to an all but literal translation of another medium rather than an adaptation of one’s style and mannerisms, it remains a singular achievement. The creation of an idiosyncratic cinematic language immediately lost to the ages again.

- Coloring 101 with Pat Boyette in „Trapped in the Cave of the Mudmen“ (Flash Gordon #13, April 1969)

Boyette was not his own colorist nine times out of ten, but he evidently had a keen eye for how color would render on newsprint as well as motion picture film. Later in his life, he researched new methods to improve the process of printing color on different paper stocks.

- „The Painting in the Tower“ (Eerie #33, May 1971)

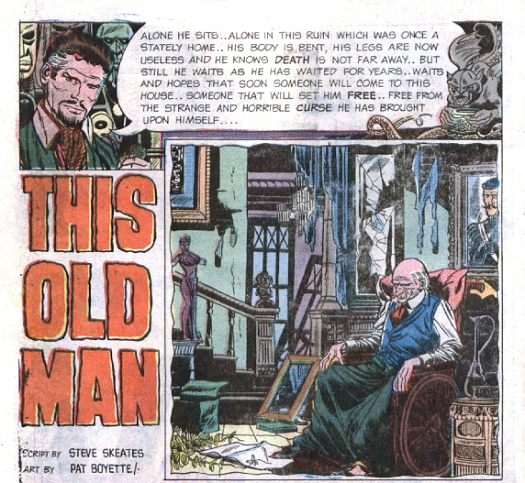

- „This Old Man“ (The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves #08, August 1968)

- With many thanks and kind greetings directed at my trusted comic book guy Markus Tump who supplied me with many of above’s plundered issues.

The Dungeon of Harrow – USA 1962 – 86 minutes – Direction: Pat Boyette – Production: Ross Harvey, Don Russell – Screenplay: Pat Boyette, Henry Garcia – Cinematography: James C. Houston – Editing: Don Russell – Music: Pat Boyette – Cast: Russ Harvey, Helen Hogan, William McNulty, Maurice Harris, Lee Morgan and many more

- „The Shining Castle“ (Ghostly Tales #62, August 1967)

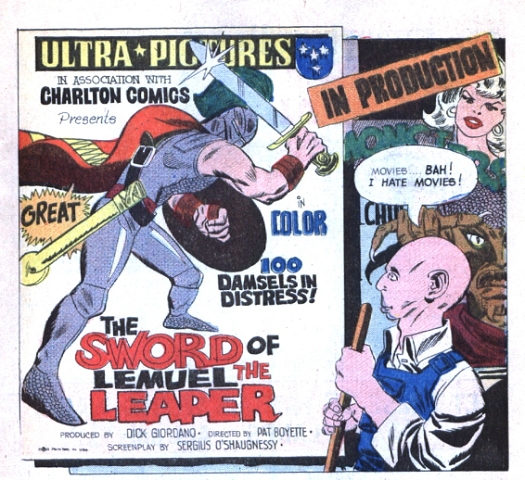

- „The Sword of Lemuel the Leaper“ (Strange Suspense Stories #01, October 1967)

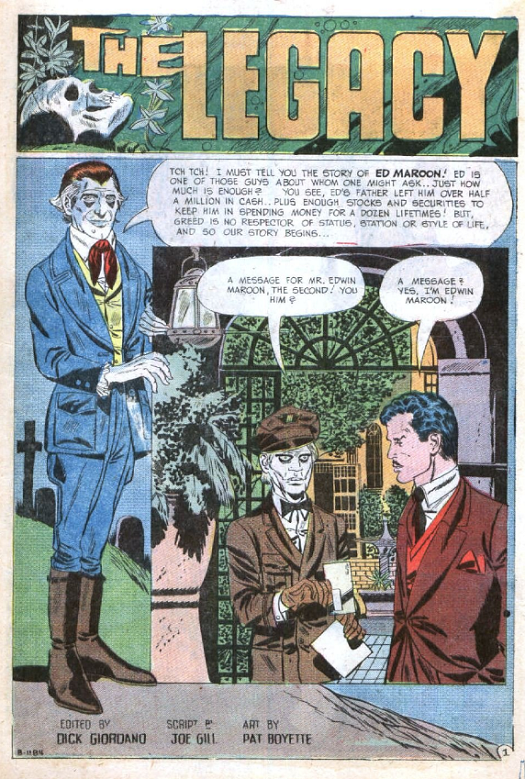

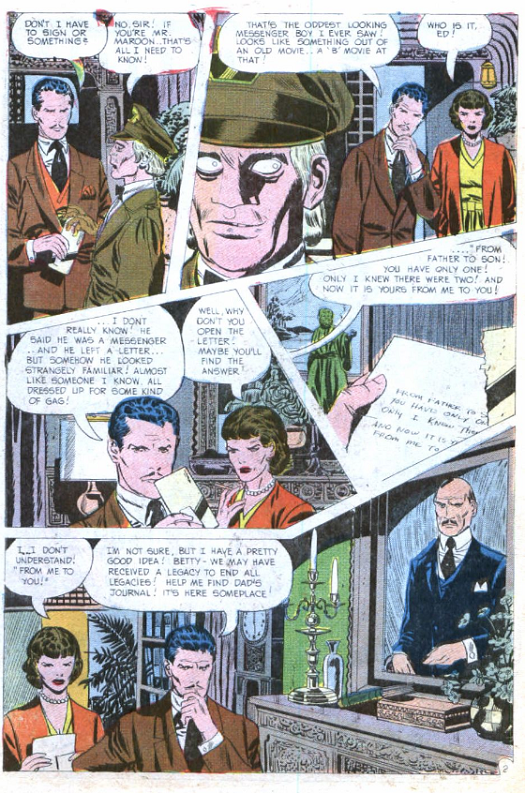

- „The Legacy“ (Ghostly Tales #66, May 1968)

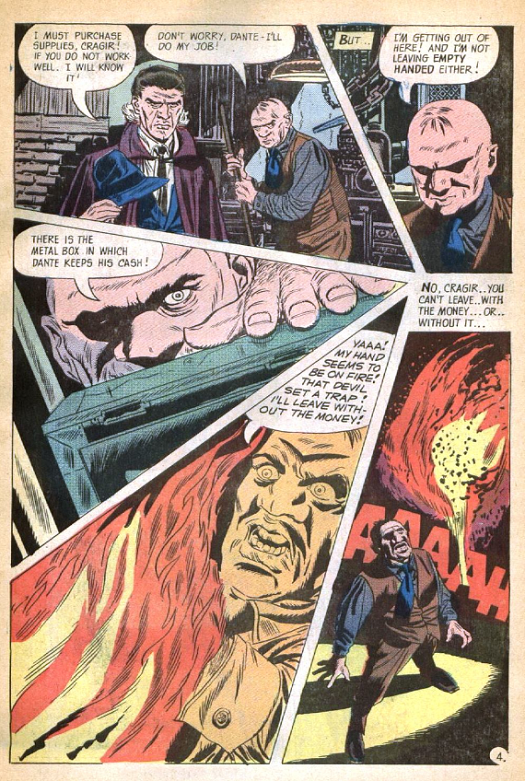

- A menacing gaze enforcing a sudden switch to counter-clockwise reading in „Dante’s People!“ (Strange Suspense Stories #03, September 1968)…

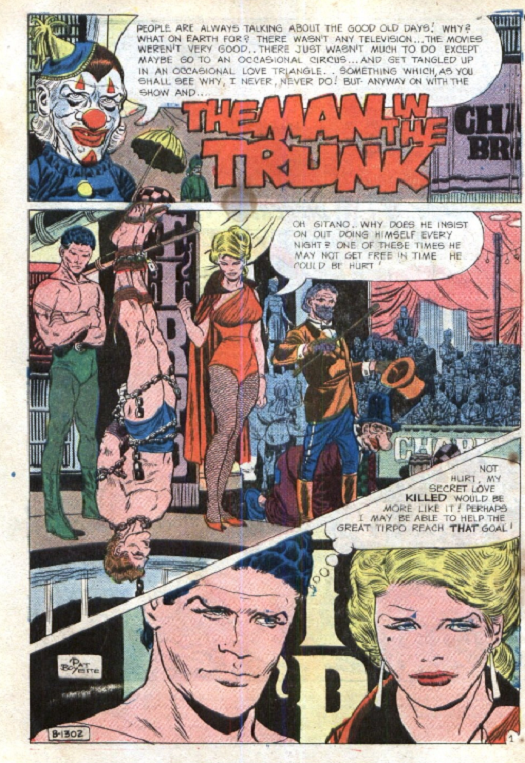

- …and a broken perspective, a whole person being exchanged and lifted upside-down between panels in „The Man in the Trunk“ (Ghostly Tales #67, July 1968).

- „Delayed Doom“ (The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves #21, August 1970)

- A typical Boyette progression through panels in „The Rescue of the Morning Maid“ (Creepy #18, January 1968) – the body’s direction is our direction.

- „Home Is Where –“ (Creepy #22, August 1968)

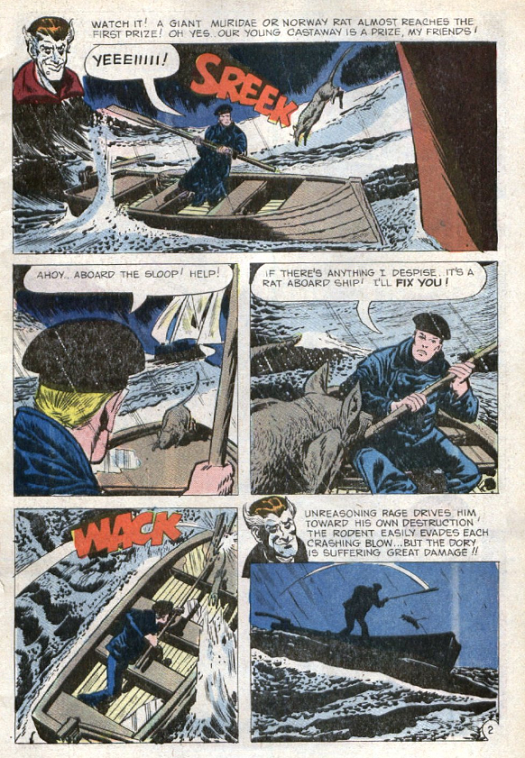

- More action panels and page progressions from „Abandoned Ship“ (Ghostly Tales #61, June 1967)…

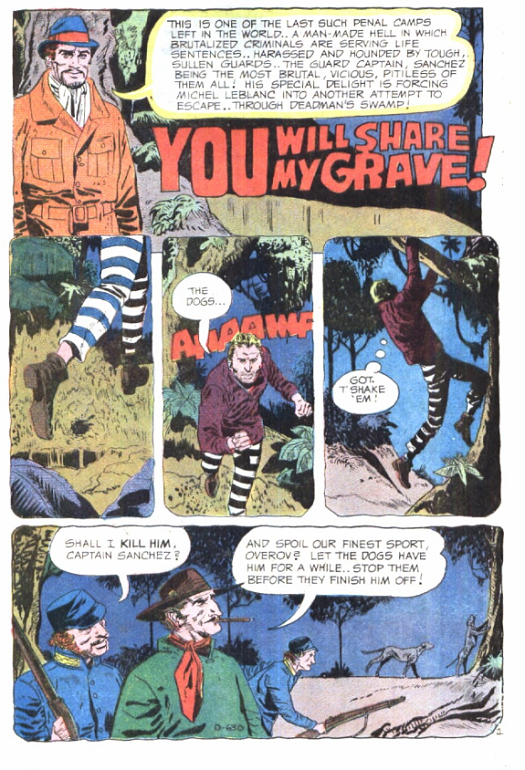

- …“You Will Share My Grave!“ (The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves #23, December 1970)…

- …“One More Time“ (The Many Ghosts of Dr. Graves #48, November 1974)…

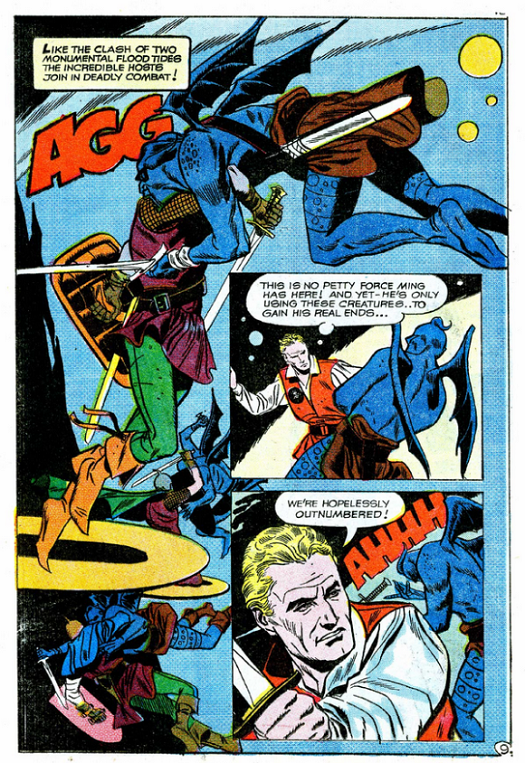

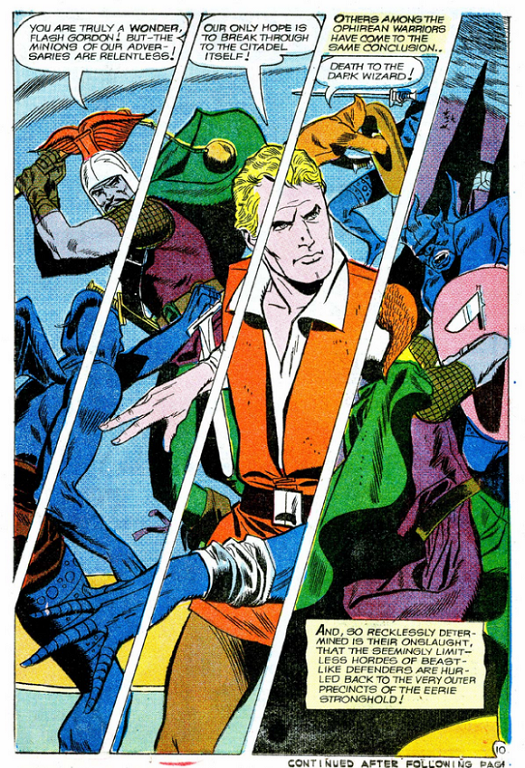

- …“Mission Into the Mystic Realm“ (Flash Gordon #16, October 1969) to fill the gaps.

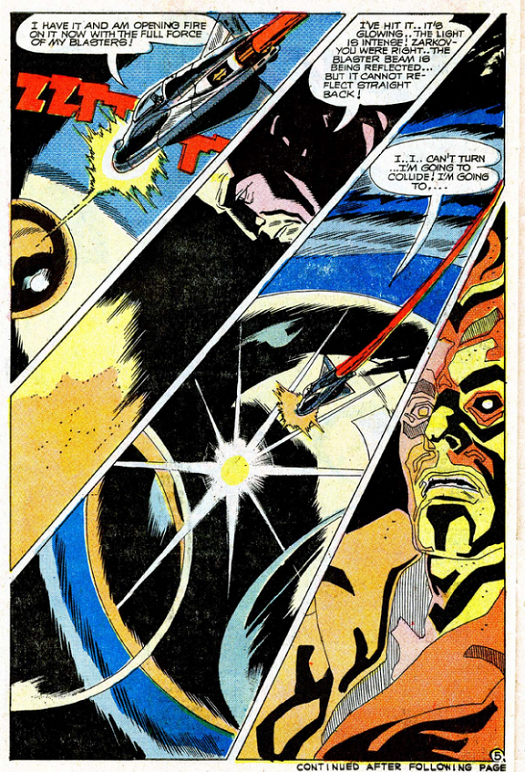

- „The Creeping Menace“ (Flash Gordon #17, November 1969)

- „Home Is Where –“ (Creepy #22, August 1968)

Kommentar hinzufügen